It happened again, I thought. A ray of sunlight landed on the kitchen counter as I watched the skin on my hands curl up in reaction to the cold water that dripped from the plates I was washing. Instinctively, I turned to the balcony, where some clothes were struggling to dry. It had rained all morning; gray clouds filled the sky, and a glimpse of clarity imprinted long shadows on the surrounding buildings. A fly entered the kitchen and flew away in seconds, and just then, I could almost swear I heard my mother’s voice advising me to close the windows because flies always try to take refuge inside of our houses. Just as people, I answered. But people don’t make awful buzzing noises and are certainly not as dirty as flies, they don’t just land on food and contaminate everything they touch. My mother laughed. Well, sometimes people are exactly like that.

“In the morning there was hope.” These are the first words of Tove Ditlevsen’s autobiographical novel “Childhood”. Memories such as this one – the sunlight bathing the kitchen, the sky’s clarity after a rain shower – would present themselves to me from time to time, but lately they had been stronger during the earliest hours of the morning. They looked like fragments of stories. “What’s your story?”, Rebecca Solnit asks in her book “The Faraway Nearby”. Lately, I have been thinking about my story, and I think it must be hidden somewhere in my childhood. I look at these fragments and often imagine myself taking them in my hands, but they dissolve right away. “The center cannot hold.” My childhood is the line that ties together central aspects of my personality, as a rope sustains clothes and bed sheets, and I often feel I pick up these details as stories. Stories I want to tell and at the same time keep to myself.

After these moments, a strange urge to write down words manifests. The fact this always happens when I am at the kitchen might be somehow related to my mother. I learned to long for something when I was still a small child. My mother worked as a primary school teacher and she was forced to live in different cities across the country. From time to time, as school breaks quickly approached, she would promise to come home earlier for the weekend. The excitement was almost unbearable, and against my grandmother’s good intentions of an afternoon nap, I’d spend hours in the balcony, trying to catch a glimpse of her old car. Sometimes, I could swear the car was there, at the beginning of the street, and I’d put my shoes on and run the down the stairs, waiting for her to stop and pick me up. Almost every time it wasn’t her, and I would watch some stranger’s car slowly disappear around the corner, my heart heavy while my grandmother would scream for me to get back inside, it’s cold and dark, come in, she’ll be here any time soon. Inside the house, my grandfather would give me pencils and a sheet of paper to keep me entertained. He worked as a photographer, and I loved to watch his hands fix an old photography or cut people’s portraits. He also painted landscapes from his hometown, fields covered with snow and empty streets, where a cat slept by the entrance of an old house. The air, filled with the smell of oil, turpentine and crayons, was silent, and the only thing you could hear was the faint sound of a lone TV set upstairs. From time to time, he would look at my drawings and say light was the most important thing to someone who paints and creates visual worlds. You have to respect it, to understand it, because if you fail to do so, you will never paint things as they truly are, but instead you will paint fake objects, fake humans, fake emotions.

Tree branches and light from my hometown.

“What’s your story?” My story is rooted in my childhood memories. Those afternoons spent with my grandfather, away from other children as I longed for my mother’s return, played an important role in feeding my imagination. When I was not drawing or reading books, I would pick up my grandfather’s pencils and crayons and turn them into characters. Instead of dolls and electronic games, I used to invent my own narratives while travelling to Oporto, Lisbon and Coimbra because of a heart condition that made me take long trips to see various doctors until I was sixteen years old. I would turn my crayons or my hand into the main hero of an epic story who had to overcome many obstacles to save the world. These formidable obstacles consisted of light poles, trash cans, trees and mountains. Only many years later did I realize that these experiences nourished my imagination. In a certain way, I learned how to be by myself by writing stories every day and every night before going to sleep.

As I often could not go on exchange trips with my class because of my heart condition, I would stay at home surrounded by books. I remember a specific trip where my colleagues visited Fátima and spent the night in the holy sanctuary. My mother was always worried about the possibility of something going wrong and not being able to help me so she hadn’t allowed me to go on this trip. Instead, I spent the weekend reading “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone”, imagining myself as Hermione Granger living fantastic adventures. I spent the weekend in my living room, the golden light entering and filling the pages with a yellow tint. From my bedroom, I could see some oak trees and listen to the singing birds outside. I loved the way the light escaped through the clouds and spread its fingers over the mountains. During those moments, I learned how to love books and stories and how they allowed me to never be alone, regardless of whatever I was waiting for – my mother’s return, next week classes or the end of myvisits to health centers and hospitals.

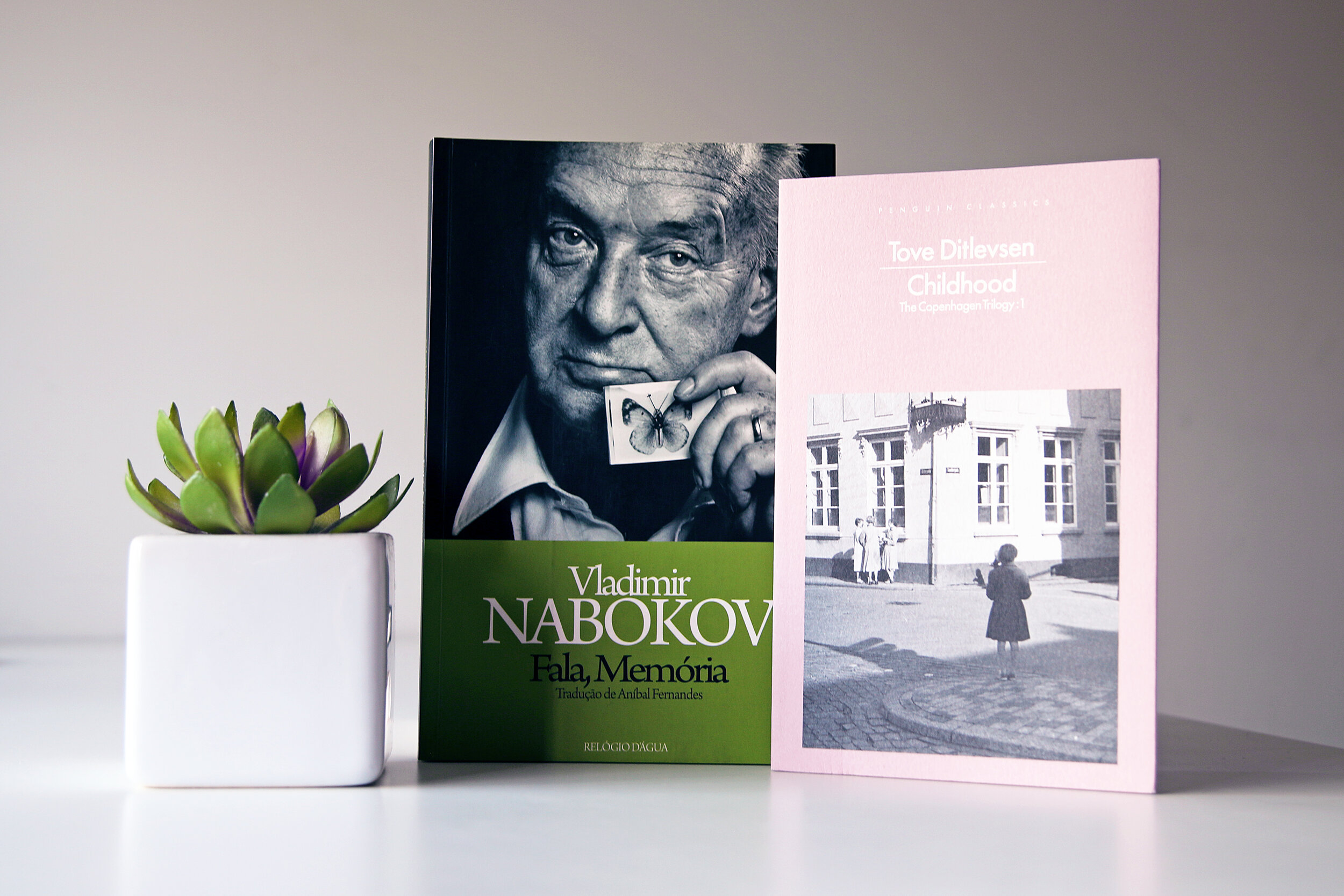

“Speak, Memory”, by Vladimir Nabokov (Portuguese edition)

A paragraph by Vladimir Nabokov in his memoir “Speak, Memory” often returns to me: “Neither in environment nor in heredity can I find the exact instrument that fashioned me, the anonymous roller that pressed upon my life a certain intricate watermark whose unique design becomes visible when the lamp of art is made to shine through life's foolscap.” I look at my childhood as the light years that covered my personality. Today, when I look away and come across a dress or other piece of clothing to be dried, hanging on the clothesline, I find a fragment of that light, of those images transformed into sensations, in words that reside in a distant yet close place. Memories from my childhood years arise from time to time, often triggered by the smallest of details: a breeze, a canticle, a curtain dancing while a summer storm echoes in the distance. Writing about our childhood is a way of knowing ourselves and some of our deepest motivations.

In “Speak, Memory”, Vladimir Nabokov described some childhood episodes, portraying his life and the permanent sense of nostalgia. This nostalgia is not always present and it is not the central element of the narrative; instead, it could be seen as a butterfly which hides its wings while resting in a flower. The main aspect are the memories as independent elements. Memories take on unique and individual contours when exposed to the golden light of time. This is the feeling evoked by this book. Nabokov cherishes childhood memories and preserves them as he did his insects (he was a butterfly collector). It is as if Nabokov had spent his life looking for these memories, transfigured in the small animals he kept. And I can't help but ask myself if this isn’t what writers are looking for - the use of words to demonstrate what a canvas or photograph can’t capture in its entirety and thus make readers feel something they thought lost?

Nabokov speaks of his essence, which goes back to childhood: the incessant search for something he has to write, that he has to put into words, transform into books (“The act of vividly recalling a patch of the past is something that I seem to have been performing with the utmost zest all my life.”) In the end, writing is reaching a place within our hidden interior, something that was exposed in the first years of our existence, but which, over time, we learned to mask. We present ourselves differently to our children, our lovers, our family members, our co-workers, and we rarely see ourselves as we are, rarely allow ourselves to feel what we were, who we are, who we will be. "Speak, Memory" is a collection of these reflections, one of the most beautiful that I had the opportunity to read.

“Childhood”, by Tove Ditlevsen

The first time I experienced grief, even before I lost my grandfather, my cat or a former boyfriend, was during a stormy winter day. It was the first week of a new school year, at a new and unfamiliar school. The old building of my primary school had been substituted by a gray concrete building, the colorful windows and drawings long gone. I now had a dozen of textbooks instead of three simpler subjects. I remember that winter as a rainy one, sunny days as rare as snow had become in my hometown. On that afternoon, my mother called my grandmother and asked her to speak with me. “I won’t be able to spend this weekend with you; the rain is too heavy and the roads have been blocked.” She asked how school had been. “Have you started studying? You must. Your childhood days are now over. You have to study hard in order to become someone of importance on day. Playtime has ended. Do you understand? Neither me nor your grandparents will be able to help you with these new subjects, English and Biology. They are too complicated for us. You have to do it by yourself, you have to study.”

We often think we can only be ourselves when we can start to live as an adult. One of my oldest and dearest friends said something similar when we were about to go to college, almost fifteen years ago. I remember she said “I am glad this is over. I want to be free; I cannot be myself when I am around my parents, my brother, his bullying behavior. I want to have my home, my own children, my partner, I want to be at home whenever I wish to. I want my independence.” Although I could sympathize with her, I felt the deepest loneliness in that moment. I wasn’t afraid of being alone, of having my own life, of having my own house. I was afraid of losing myself. All the things that surrounded me as a child, the mountains, the gardens, the view from my window: all those things would be lost, trapped somewhere and inaccessible to me. Studying, working, having a job; everything seemed to carry me away in an irretrievable way, just as the train Mary Ventura took in “Mary Ventura and the Ninth Kingdom” by Sylvia Plath.

“Everything during this time makes a deep, indelible impression on me, and it’s as if I’ll remember even completely trivial remarks my whole life. (…) I’m seized by a vast sadness.” Tove Ditlevsen wrote these words when she realized her childhood was coming to an end. It is curious how she felt it so deeply. In her small book, she seems to hate those earlier years of her life, feeling trapped by her mother’s influence, her brother’s bullying behavior and her father’s indifference. However, when she realizes she will soon have to start working and providing for herself, perhaps even having to put her poetry work aside, she weeps and feels a vast sadness that will accompany her life.

“Childhood”, by Tove Ditlevsen

What does it mean for a person to have their childhood end? For Tove Ditlevsen, it meant she had to lose a friend. It also meant she had to start finding a job instead of studying. Just like Lila Cerullo from “My Brilliant Friend”, her childhood stopped the moment she was supposed to start working to help her family and support herself. It meant she had to marry someone, someday. It meant she had to say goodbye to herself; her true being. For me, it meant I had to stop longing for my mother’s return, I had to stop painting, drawing and writing when I was by my grandfather’s side at his workshop.

As I sit in the kitchen, looking outside, the leaves dancing and the wind growing stronger, just like Truman Capote described them in “The Grass Harp”, a fictional work inspired by the author’s childhood memories, I think about the memories and the stories that once populated my existence. Those memories are mirrors of my soul, my deepest “intricate watermark” that will accompany me all my life. I no longer feel grief, sorrow or nostalgia. I know I read and write in order to be close to myself, my true being, the one who resides in stories and words. The teacup I hold in both of my hands is warm, the clothes have not dried. Maybe it will rain again. And I cannot help but smile when I remember Tove Ditlevsen’s last words in her novel:

“I read in my poetry album while the night wanders past the window – and, unawares, my childhood falls silently to the bottom of my memory, that library of the soul which I will draw knowledge and experience for the rest of my life.”