When I was eighteen years old, I decided to become a doctor. My main goal is not to scrutinize why I became a doctor, but I have to say it was a hard path. When I think back on those times, I guess the most difficult thing wasn’t going through horrible anatomy exams, nor those awful days spent studying, but rather noticing lack of empathy between doctors, healthcare professionals and medical students. After a while, I started to feel somewhat numb. And I could understand why everyone around me felt the same: there was this horrible pressure to do things quickly, to take care of 40 patients every morning, to study, to learn new things and, at the same time, to maintain a personal life.

I started to believe everything would get better when I’d become a resident. But after medical school was over, I realized I was completely wrong - I now had two difficult tasks to complete simultaneously: studying and working. On top of exams, presentations and a 40-hour work schedule, we also had to take care of real patients.

I remember clearly my first months as a primary care resident; I had to struggle to keep my sanity while working at full speed and at the same time keeping in mind I was dealing with real people in front of me. These people had problems, they were suffering, sometimes they were scared. And some of my colleagues reported even worse working conditions: they would tell me about their 100-hour work schedule, their nocturnal work in the ER department and how tired they were.

Being a doctor requires endeavoring through a hard path but I’ve found that some things make that path bearable. And reading is definitely one of them. When I was a student, I wasn’t really a fan of non-fiction books. However, over the time I realized that these books helped me understand some important concepts and even remember others I had forgotten. I often return to these books because they help maintain alive the empathy I have towards patients. And that is very important, especially in these difficult and challenging times, when bureaucracy seemingly overwhelms our whole day.

When I started my first year as a real doctor, I was not certain which kind of doctor I wanted to be. In Portugal, after medical school, we are required to spend a whole year rotating through different medical specialties as junior doctors. We usually spend that year trying to figure out what kind of doctor we want to be - surgeons, pathologists or cardiologists, for instance. I always thought I’d become a psychiatrist or a rheumatologist, but I started to feel somewhat lost. I didn’t enjoy the hospital wards and I didn’t like the idea of being a specialist. Plus, I had never enjoyed the emergency room departments nor the complicated techniques. I loved talking to people, understanding their emotions, their stories and the suffering that came with them. However, I kept thinking “I studied so much, I should choose something good for my life. Maybe a place where I could earn good money and have a nice career.” And it seemed as everyone around me felt the same way.

Fortunately, I had some amazing colleagues who helped me to realize what I really wanted. At the same time, I came across with “Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End”. There are several reasons that make this book so special. Besides being my first non-fiction medical book, it helped me to understand what I wanted. After reading it, I realized I was too focused in treating people, saving them and doing whatever I could to keep them alive, even if that meant unintentionally harming them. I finally understood what I really hated about hospital departments: we were too focused on the disease process. Instead of hearing patients properly, valuing their lives and listening to their choices and opinions, we were doing everything we could to prevent bad outcomes, even if that meant losing our empathy. “Being Mortal” isn’t a plea for assisted death; instead, it raises questions about patients’ autonomy, doctor-patient relationships and patients’ preferences.

“A few conclusions become clear when we understand this: that our most cruel failure in how we treat the sick and the aged is the failure to recognize that they have priorities beyond merely being safe and living longer; that the chance to shape one’s story is essential to sustaining meaning in life; that we have the opportunity to refashion our institutions, our culture, and our conversations in ways that transform the possibilities for the last chapters of everyone’s lives.”

― Being Mortal, Atul Gawande

Whenever I have the opportunity to recommend books to healthcare professionals, I always recommend “Being Mortal”. For me, it is a very important book, because Atul Gawande gently remembers us that a person is not and cannot be defined by a disease. Whenever we come across important decisions about life, death and treatments, patient choices are very important. And this is a fundamental aspect in medicine, no matter if you are an internist, an urologist or a pediatrician.

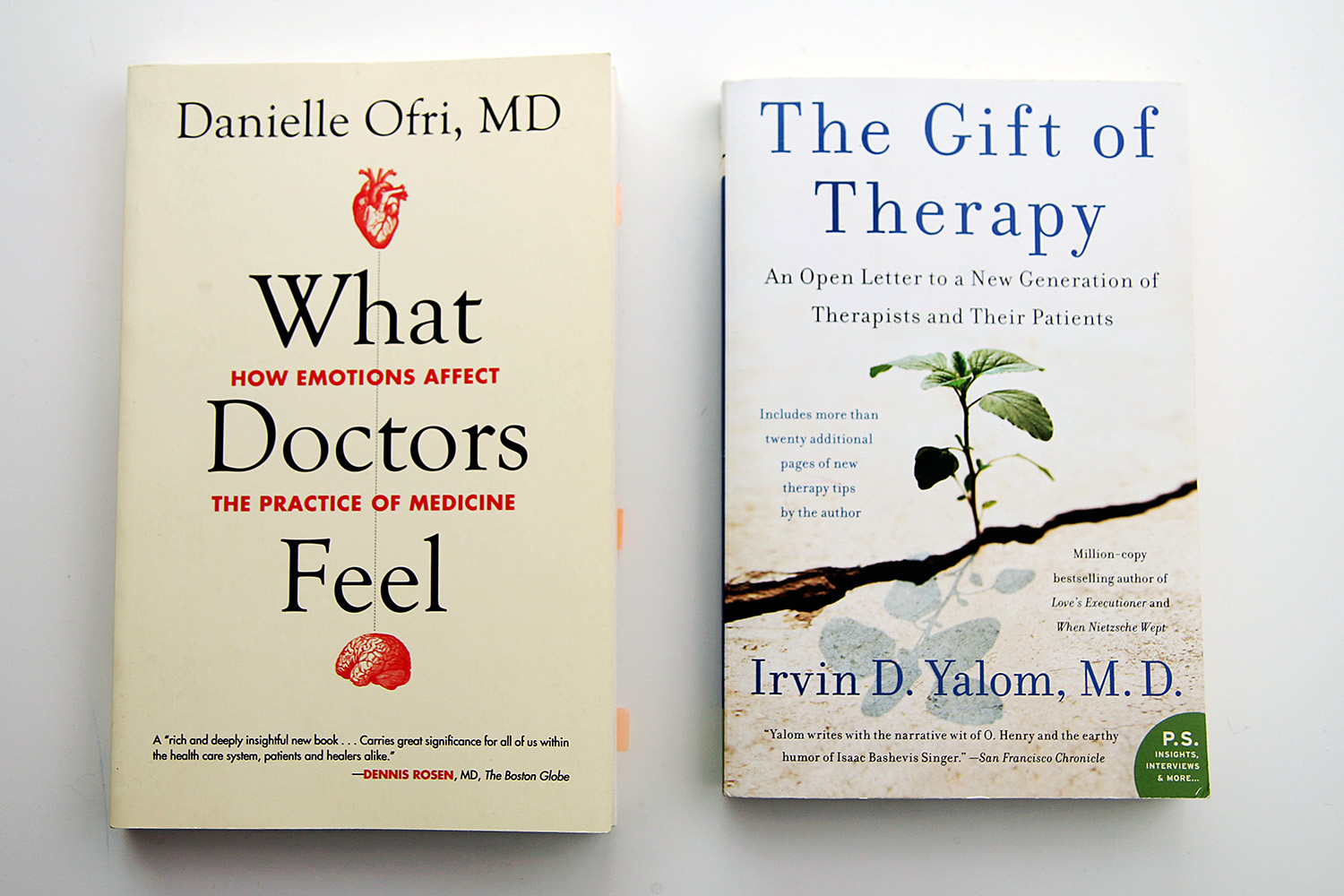

I decided to become a primary care doctor. A few months later, I was already consulting many patients all by myself. This was a challenging process and a period of adjustments. But above all, it was then that I realized just how poorly my student years had taught me clinical communication skills. Everyone knows how to talk to people, but not everyone has to know all the communication tools we can use to express ourselves and make our patients understand we are there to help them. Those first months were also difficult because I started to struggle with many emotions. I had been taught to suppress my feelings; a doctor shouldn’t show signs of weakness because he or she has to be strong for their patients. When I read “What Doctors Feel: How Emotions Affect the Practice of Medicine”, I could finally understand that bottled up emotions may lead to terrible outcomes. Danielle Ofri explains the importance of assessing our emotions. It also explains how healthcare professionals can use some communication techniques (such as empathy, silence and active listening) to connect with their patients and improve their outcomes.

“Empathy requires being attuned to the patient's perspective and understanding how the illness is woven into this particular persons' life. Last - and this is where doctors often stumble - empathy requires being able to communicate all of this to the patient.” ― What Doctors Feel: How Emotions Affect the Practice of Medicine, Danielle Ofri

I read this book after I started attending a Clinical Communication course and it helped me immensely in understanding that these were important topics that unfortunately aren’t written in many medical books. There are several important and real stories in “What Doctors Feel” regarding stresses of medical life and how they affect the medical care that doctors offer their patients. It also explains how emotions permeate the doctor-patient relationship.

Around the same time, I found an amazing book written by Irvin D. Yalom. “The Gift of Therapy: An Open Letter to a New Generation of Therapists and Their Patients” is an extraordinary reading, not only for psychotherapists, but also for every doctor. Irvin D. Yalom writes several short stories and essays regarding how to use an effective therapeutic relationship to talk with patients about difficult issues like death.

“Look out the other’s window. Try to see the world as your patient sees it.”

― The Gift of Therapy: An Open Letter to a New Generation of Therapists and Their Patients, Irvin D. Yalom

A few autobiographical books also helped me a great deal. “On the Move: A Life” was written by Oliver Sacks, a British neurologist and one of my favorite medical writers. There are many aspects in this book that go beyond medical issues, but it is a wonderful read. Oliver Sacks writes about the importance of listening to people and treating them as real human beings and not just clinical cases. I was amazed by his life path and his career as a doctor. He shares several interesting stories, but also thoughts about being a doctor and caring for people who are suffering. He also explores difficult subjects, such as suicide, depression and addiction. His words reflect how empathic he was towards his patients:

“Patients were real, often passionate individuals with real problems—and sometimes choices—of an often agonizing sort. It was not just a question of diagnosis and treatment; much graver questions could present themselves—questions about the quality of life and whether life was even worth living in some circumstances.”

― On the Move, Oliver Sacks

Another great autobiographical book I’d recommend is “When Breath Becomes Air”. This book was written by Paul Kalanithi, a 36 years old neurosurgeon who was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. As a resident, it is easy to empathize with Paul’s words. He tells us about his internship, his struggles and doubts, his successes and victories. As a neurosurgeon, he faced many difficult diagnoses, so it is interesting to read about some aspects related to communicating bad news. Throughout the book, we follow Paul Kalanithi giving his patients the empathy and attention they needed, especially when he had bad news for them.

“The physician’s duty is not to stave off death or return patients to their old lives, but to take into our arms a patient and family whose lives have disintegrated and work until they can stand back up and face, and make sense of, their own existence.”

― When Breath Becomes Air, Paul Kalanithi

I find “When Breath Becomes Air” special because every doctor who reads it is able to put him or herself in Paul’s shoes and understand not only a doctor’s point of view, but also a patient’s point of view. Paul Kalanithi did that too: he was a doctor facing difficult diseases but also a patient with a terrible path ahead. We follow Paul confronting not only a terminal illness, but also an identity crisis. As his 20-year plan after his residency, his family, his aspirations slowly vanish - he fells he has to give up everything he fought for. As an intern, a doctor and a person, I felt moved reading his words about suffering and courage. It also showed me we can't control every single aspect in our lives, but we can still choose how to approach it and decide how we really want to live.

Finally, I will recommend a very different book. I strongly believe that literature can help everyone understand difficult emotions and situations. Whenever I face a situation I cannot fully understand, I try to read more about that. For that reason, I keep “The Novel Cure: An A-Z of Literary Remedies” as an useful aid. It features many different suggestions regarding lots of topics. It is mainly a list book, so I use it whenever I want to read about specific themes, such as “fear of flying”, “having cancer” or “guilt”.